Official Finisher, 98, 99, 00, 01, 02

Bolts of lightening are slamming into the mountains and the windshield is being pelted with rain from the giant thunderheads filling the evening skies, as our mini-market laden van rolls south along Highway 395 towards Lone Pine and our eventual destination in Death Valley. Each year along this stretch of pavement, it becomes starkly clear, that soon I will be faced with the momentous challenge of running the toughest footrace in the world. Although I have worked very hard and I am completely trained, the harsh weather surrounding us reminds me of the enormous task ahead. I am confident, apprehensive and scared to death.

Every July ninety long distance runners from around the world are invited to compete in the 135-mile Badwater Ultramarathon. This event starts at Badwater, CA the lowest spot in the United States. It snakes through Death Valley and crosses three mountain ranges before finishing at the Portals on the flanks of MT Whitney. To receive a coveted belt buckle one must finish in less than forty-eight hours. This will be my fifth consecutive Badwater race.

The next day at the pre-race meeting in Furnace Creek, I am inspired by the presence of Lisa Smith and Marshall Ulrich, two of my heroes and Badwater ultrarunning giants. Everyone in the building chokes up when the first man to complete Badwater in 1977, Al Arnold, gives an emotional speech.

To prevent congestion in this National Park there are three starting times (6:00 am, 8:00 am and 10:00 am) with twenty-seven runners in each group.

While driving in for the ten o’clock start I am surprised to see United States Marine Corp, Major Maples, (well known for his multicolor Badwater barfathons), in second place only a few feet behind the leader. He said he would be taking it easy this year. It must be the Marine esprit de corps and all that stuff. I hope he makes it

The moment that everyone has been waiting for is now only minutes away. To preserve these memories truckloads of photographs are taken as we straddle the starting line and stare into the teeth of this most difficult race. During the next few days of roller-coaster highs and lows, having a good time is guaranteed, as well as, getting blitzed by plenty of heat, misery and pain. But, as far as finishing goes, it will be a coin toss, a crapshoot, and the luck of the draw. Yet, we are all still here, drawn to this race like a moth to a hot light bulb. Even though it is already 110-degrees, I get goose bumps and butterflies when the National Anthem is played to honor all the runners. It is good to be back.

The word is given and off we go. “Start slow and then taper,” said the legendary San Franciscan marathoner Walt Stack. Okay. Plan A is to take it fairly easy for the first 42-miles to Stovepipe Wells. If I am conservative during this part of the race I should be able to attack the rest of the course. Sounds good anyway.

My crew, Christine Webb, Lina and Jacqueline Young and Jason Hunter will leapfrog me every mile in the van and attempt to keep me hydrated and well fed. Trying to keep me cool, they will use a super-soaker to wet down my Sun Precautions hat and jacket during the extreme heat of the day. For the first time my beautiful wife is here to help crew the entire race. I told her that if she came along this would be my last Badwater. I don’t think she believes me.

During the early part of the race when we are all full of energy and clicking on all cylinders we run past the colorful landmarks of Furnace Creek, Devils Cornfield, Devils Golf Course and Dantes Point. It’s almost impossible to believe that this barren and arid basin was once filled with water.

Even though the temperature begins to climb into the 120-degree range, I am running at a comfortable pace and having a good time. Fortunately I have started this race relatively healthy. Although I am still pestered by the Achilles tendonitis I developed in last year’s race, it should only be a minor nuisance. At the start of other Badwater races I have been handicapped with inflamed sciatica, stress fractures and a broken toe that I had crunched on a chair leg the day before. Still, I have managed to finish every race.

Through the grapevine we learn that a British runner (promoting Roger Rabbit) started this race in a bunny suit, including the head. He had already collapsed from heat exhaustion. He was evacuated to a nearby hospital. He recovered, but by mile nine the race had claimed its first victim.

This year more than ever the runners are spaced farther apart and there are periods of time when no one is in sight. At times, while I run alone, I listen to the sounds of silence that are gently rising from this great sprawling salt basin, which is surrounded by incredibly chiseled mountains that are brushed with sparkling burgundy and other softer rainbow colors. I am easily hypnotized and totally engulfed by the immense beauty of Death Valley. This place is one of the most picturesque on earth and is a gift for man to treasure. It is a litmus test for one’s spirituality. It is a privilege to be running here.

There are little piles of reminders along the road noting that other runners are having a tough time keeping food and liquids in their stomach. This is never a good sign because vomiting too much lends itself to severe dehydration and an early exit. I haven’t seen any colorful displays yet, which means the Major must be okay.

For brief moments during the day and into the night, I run with my friend Paul Stone. He is crewed by his lovely wife, Abby, a budding cinematographer. She is worried when he is slowed by some horrid stomach problem, but I know that Paul’s tenaciousness will fight this thing off and she can videotape him and everybody else at the finish.

While taking a drink around mile-20, something unusual happens. I knock out one of my front crowns and break the tooth behind it with my water bottle. Strange, I don’t remember this in my race plans.

Just before the Beatty turnoff (mile-28) I catch Chris Frost who is captivated by the super soaking that my crew was giving me. My crew relented and gave him our spare soaker to keep himself cooled down. I hope it helped. I was also glad that mine kept working.

The last five miles into the small resort of Stovepipe Wells (mile-42), where one has a grand view of the famous Death Valley Sand Dunes, which are now stunningly shadowed by the early afternoon sun, has always been the hottest part of the race. This year is no different. Even as I begin to wilt in the 126-degree heat that can be seen undulating from the surface of the road, I continue to run at a brisk pace knowing that a shower at the motel is beckoning. Although it is enticingly inviting, I manage to stay out of their small pool. For unknown reasons jumping in the water has given other runners and myself incredible cramps. I have seen runners go into convulsions and know others who have vomited parts of their stomach lining. For these runners it becomes a frustrating early exit.

After a shower and a 15-minute respite to snack on peanut butter, olives and power gel, I begin the sixteen-mile long and relentless trek up the tough grade to the top at Towne’s Pass.

Except for the overwhelming record setting 130-degree temperatures during my first Badwater race in 1998, when my toenails exploded like kernels of popcorn, the first few miles out of Stovepipe Wells were the hottest I have ever been in my life. A gentle mountain breeze was picking up the 200-degree radiated pavement heat and blowing it right in my face. Nor was there any relief walking on the hot berm of sand on the shoulder of the road. I had trained for months in a 170-degree sauna in order to adapt to this heat. In a sauna you can cool off by leaving the room, but out here there is no escape. The heat clings to you and cannot be washed away. I felt like I was in a frying pan and would soon melt.

My race plan was to jog at a slow pace to the top of this grade. Unfortunately the extreme heat was taking its toll. I was having trouble breathing in the oven-like air and my legs began to feel like heavy logs. I became extremely fatigued and even walking was torturous. But I knew from my 25-years of running that even when the body is subjected to extreme conditions, it has a miraculous way of recovering. It just has to be fed the proper food and fluids. As I inch forward, I consume lots of PowerAde, water and Power Gel. As it starts to get dark and cools down to a pleasant 100-degrees, I begin to feel better.

Somewhere around mile forty-eight, I came upon one of the South American runners who I thought had a chance to win this race. He and his crew were sitting on the side of the road commiserating and consoling each other. The strained look in their eyes told me that he was finished. So much training, preparation and dreaming and now it was all over. The harsh day had taken another victim. He had rolled snake eyes with 88-miles to go.

Although I felt more rested, I knew that I could not run all the way to the top. I was forced to resort to plan B. I strapped on my Sony CD player and I listened to my favorite music. I would run during a song and then power walk the next one. This alternating scheme worked so well that I was able to charge up the mountain pass. My crew said that all that they heard, for the next two days, was Arthur Webb merrily singing along and creating havoc with the music from the Simon and Garfunkel Greatest Hits Album.

By the radiator stop at the top of Towne’s Pass (mile-59) I felt a ten-minute well-deserved catnap was in order. Mistake number one. After a few minutes on the cot, my body was hammered everywhere with incredible cramping. My body was suffering from severe dehydration. Knots the size of walnuts began to surface first in my hamstrings and then in my stomach and quadriceps. Any movement caused a dozen more cramps. Instead of letting me bend up like a pretzel, my crew yanked me to a standing position. After walking around and consuming large amounts of electrolytes my system stabilized.

Then I began the thirteen-mile segment to the Panamint Springs Resort. The first six-miles are quick as I run down the mountain pass in the cool of the evening and then face the more difficult seven-mile run across the Panamint Valley. Near the bottom I run into Kari Marchant who is suffering but still full of energy. After a few minutes of censored chitchat, I charge ahead into the dark of night.

It was time for a refill of inspiration as I catch Rick Nawrocki by the Panamint salt flats (mile-65), which were iridescent from the glowing full moon. This man, his life in peril from an invasion of cancer and suffering from the side effects of chemotherapy, had finished the last few Badwater races. Fortunately he has been cancer free for a year, but now is struggling with a groin pull and other problems. If you ever want to really get emotional just wait for Rick at the finish line. He will be there. This gentle giant will never quit. Rick is my super hero.

After reaching the Panamint Springs Resort (mile-72), I stopped in the hospitality room for a bathroom break. Then I sat down in the parking lot and waited for my crew to make the scrambled eggs that I always crave. Whoops, another big mistake. Ten minutes later I felt woozy and blacked out for a few seconds on the desert floor. While I was laying low and looking around at the sympathetic eyes of my wife and crew, I flashed on the dreaded DNF (did not finish) column during a brief weak moment.

I could feel the tension among my crew as they attempted to figure out how to help me. They have been working hard for the last twenty-four hours catering to all my needs. They are also tired and weary from all the blistering and punishing heat. I tell them that salt and water is what my system needs the most. Dehydration continues to be the problem and I will be redlining it the rest of the race.

Although I was feeling awful, I knew that I was never going to quit. The kids that I run for at the Valley of the Moon Children’s Home, a crisis center for abused and abandoned children in Santa Rosa, CA, were following this race on local radio and on the Badwater race website. How could I ever face them if I folded up my tent and went home. They have already seen enough giving up in their lives. Besides, my few hours of suffering would be nothing compared to the anguish that some of these kids will have to face their entire lives. Also, scrawled on the side of my van was the motto, “The objective is to finish. We didn’t come out here to quit. Do it for the kids.” This was strong medicine and a powerful incentive.

My biggest concern was that besides the Crystal Geyser water, PowerAde and my secret favorites, Cheetos, Starbucks Frappuccinos, and O’Doul’s, there was nothing in my goody filled van that would satiate me. I even spat out the eggs I was craving. Remember the saying food, food everywhere but nothing to eat?

Time for Plan C. Get to the finish line the best way you can. I got off the ground and started the gigantic snail-like struggle up the extremely steep eight-mile mountain pass. The first few miles are sheer torture as the disoriented, nauseated and physically worn body just wants to stop, lay down and sleep. I had just slammed into the well-known “Marathoner’s Wall” and now was attempting to drag it up this hillside. In order to finish, I had to somehow dig down deep to find a way to continue to push forward.

Amazingly our cell phone rang. It was my father-in-law and sister-in-law driving in from Los Angeles checking in on our progress. I told them to stop at a Subway and bring me an assortment of cheese and meat sandwiches. By the time I reached the summit at Father Crowley’s Point (mile-80) they were just arriving. Unbelievable. A special delivered catered lunch out in the middle of the desert. I sat on the stoop of the van (there will be no more lying down) and gobbled a sandwich and washed it down with Ensure. Feel better? Yes. A Small miracle? Maybe.

A few miles later, where the road snakes along the side of the mountain and we have a spectacular view of a mini-like Grand Canyon, an F-15 on a training mission passes just above our heads. It was amazing to watch this silver bird sailing along the canyon walls. Near the bottom it went vertical for a few seconds then rolled over several times and disappeared into the horizon. Minutes later as he repeated the exercise we began jumping up and down honoring this awesome air display. Stay tuned Saddam.

The next ten miles of gently rolling hills should be easy to run but they are not. Having to face another hot day, the sleep deprived and overworked system begins to fight back. Foods in liquid form are poured down the throat and chased with gulps of water since chewing and swallowing have become difficult. It is ironic that we have to eat and hydrate constantly to maintain, while the myriad of fragile desert plant life everywhere in this valley struggles for survival all summer long on only a few drops of water. And we think we are tough.

I am still struggling at the Darwin checkpoint (mile-90), yet I somehow manage to run the next ten miles of slight down hills before stopping and taking group pictures at the 100-mile mark. Usually from this vantage point one can view the Owens Valley ringed by the massive granite walls of the Eastern Sierras and the equally impressive White Mountains. But not this year. The smoke from a gigantic forest fire on the western side of the mountains had blanketed the region. A notable race landmark, the burg of Keeler (mile-108), which is nestled on the edge of the dried up Owens Lake, was also blotted out. Not all news is bad. Only thirty-five miles to go.

Near Keeler the setting sun and rising moon are full and brilliant and orange from the fog-like smoke. Somewhere in the distance, in this Mars-like landscape, there is the clanking of a piece of machinery. From the dark crevices of the tired mind strange movements begin to appear and at any moment I expect to see Star Wars creatures crawling across the eerie scenery.

Dinner (a can of cold Campbell’s Chunky soup) was served on the side of the road at Keeler (a.k.a. Killer). Four years ago at this same spot it was 125-degrees at six in the afternoon. I was suffering from heat exhaustion and had to be wrapped in an ice bag for twenty minutes before I could continue. Two years ago CalTrans paved five miles of road along this stretch earlier in the day. The soles of my running shoes began melting as the 200-degree pavement began to skewer me.

Reinvigorated by the sense that the end is relatively near, I run the last 14-miles into the city of Lone Pine. Before the final climb, I socialize with Lisa Smith’s husband, Jay (Mr. Mom), at the Dow Villa Hotel while my crew tended to a minor emergency.

As Jason and I make the left turn on the MT Whitney Portal Road for the thirteen-mile climb to the finish line, we see the large white LP (Lot of Pain) lettering appropriately emblazoned on a knoll high above the amazingly crafted Alabama Hills. Minutes later, in total darkness, a profound tic-tic-ticking began to close in from below. Heck, we had just started this climb and something was already after us. Fortunately it was just Major Maples tapping the pavement with a stick in each hand for cadence and balance. With his determined look and quick pace, he appeared to be storming the beach. He would get his buckle. Semper Fi Mr. Maples.

Weariness is again creeping in as I begin to think and speak in fragments. I spend half an hour trying to recite (race winner) Pam Reed’s Macbethian approach to this event, “If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well it were done quickly.” But it only gets mixed up with other Shakespearean stuff. Although I never did manage to say it correctly, it will be my theme song for next year.

Suddenly from the pavement up ahead came this huge ghostly glob of transparent goo with a face full of beady eyes. It was heading straight for me but I was able to dodge away. Then little humanoids began to appear along the road and strange animals were crouched amongst the fern-like shrubbery waiting for us to falter. Jason also sensed their presence as we both picked up the pace and managed to pass safely. Several years ago at this same spot a group of Yetis and a flock of prehistoric pterodactyls were escorting me up this mountain. Hallucinations or not, this is great stuff.

Just after our narrow escape I catch Toni Miller from the six o’clock start. She was concentrating hard and was handily moving up the mountain. Two more hours at the current pace and she would buckle. For encouragement and confidence, I praised her on the great job she was doing. I added that the last bit of struggle and suffering would be soon forgotten while the finish line and her prized buckle would last forever. Then I went twenty feet ahead at a slightly faster pace and started cutting all the corners to save precious time. I was hoping that she would follow suit, which she did. With two miles to go I told her that the sweet smell in the air was the finish line. Nothing was going to slow her down now.

When she realized that the end was near, her emotions began to take over. Toni excused herself for all the tears. Forget it. Cry a river. This is the best part. She wanted me to cross the finish line with her. I begged off. This crowning moment was hers. It was the reward for all the hard work that she had done. I stepped aside and watched Toni and her friends break the tape in forty-seven hours and thirty-nine minutes. It was worth the trip just for this touching moment. Toni would have made it without my intervention; I just hope I helped make it a little easier.

Minutes later I cross the finish line with my excited crew. This most incredibly difficult forty-three hour mission is finally over. The next few minutes are filled with enormous pride and satisfaction as the yelling and weeping spill forth. This celebration is the culmination of a successful yearlong journey that thoroughly tests you mentally, physically, emotionally and at far greater depths where the will and soul reside. I firmly believe that if one can finish this race than anything is possible. In my little running world completing Badwater is as good as it gets.

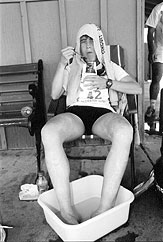

After crossing the finish line the body that has struggled and worked so hard needs to recover and immediately begins to shut down. Only minutes before I was trudging up a difficult thirteen-mile grade and now I can’t walk five feet. I am literally poured into the van and we head down the mountain. There is a string of runners pushing up the hill attempting to fulfill their dreams. I think they are all going to make it.

After we arrive at the hotel, my shoes are pried off and the socks are peeled from my severely blistered and swollen hamburger-like feet. Unable to sleep from a post-race buzz, I start to shuffle down Main Street. Seconds later I trip on a small rock and do a belly flop in front of a group of tourists. As I was on my knees, wiping the gravel and dust from the strawberries across my elbows, one of the spectators gives me a seven point five for the sidewalk springboard dive. To prove it was no fluke I did it again one block away in front of the post office. I better get to bed before I really hurt myself.

The next day, during the long drive home, the adrenaline begins to dissipate and my frayed mind and body are totally consumed by extreme fatigue. Although my thoughts are many miles away and this race seems just like a dream to me now, there is still a small pocket of endorphins racing around deep inside that are already looking forward to the 2003 Badwater race.

Although it will take several months to fully recover, I can’t wait to start the 120-miles a week running regimen. I also look forward to the daily Nautilus workouts and the baking sessions in the sauna at the 24-Hour Fitness Center. Even at 61-years-old, I should do better. I believe that I have finally figured this race out. And, as they say, the sixth time is a charm.

I can’t wait for the summer training sessions when I can hang around with all my friends and heroes. The camaraderie here is top-notch.

I can’t wait for the preparation and the journey across the desert when we drive to the starting line and everyone is full of energy and excitement.

I can’t wait to run through all the beauty and majesty that is in Death Valley and on Mt Whitney. This place refreshes my faith and helps me feel young and alive.

Although someone once said that the special ring to this Badwater race is similar to the tolling of Edgar Allen Poe’s “Bells”, I can’t wait to come back.

Thanks to Race Director Chris Kostman and his support team at AdventureCORPS. This was your best race.

Thanks to Ben and Denise Jones for all your help and compassion. Everyone loves you.

Thanks to my crew for suffering along with me in the desert. Without your help I would not have made it.

Thanks to Ted and Suzie’s Deli Express. I promised I would do anything for those sandwiches. Yes, I am still going to paint your house in September. (I did).

Thanks to all the Santa Rosa Postal Workers, Post 21 of the American Legion, KMGG-FM, KSRO-AM and Channel 50 for all their support and contributions for all the kids and the special interactive program at the Valley of the Moon Children’s Home.

Thanks to my wonderful and understanding wife. Honestly next year will be my last Badwater race. Maybe.

It was indeed an honor to be part of the toughest footrace in the world the Sun Precautions 2002 Badwater Ultramarathon.